- William Digby Prosperous British India Traveller

- William Digby Prosperous British India Wikipedia

- William Digby Prosperous British India Coin

- William Digby Prosperous British Indian

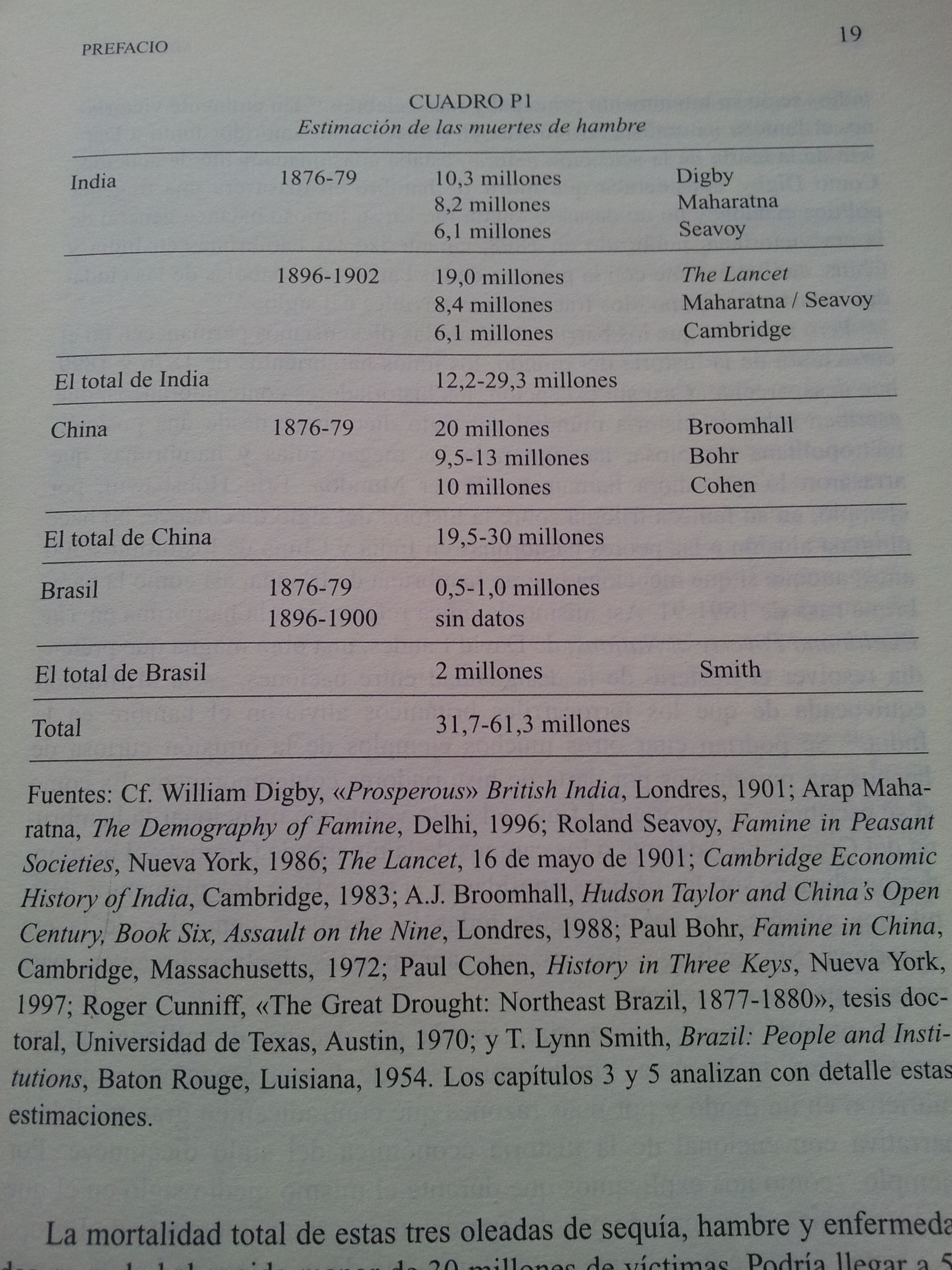

William Digby moved to the Indian subcontinent in 1871 and worked as a sub-editor in The Ceylon Observer., and as the editor of The Madras Times in 1877. He also worked as the editor of the Liverpool and Southport Daily News in 1880 and that of the Plymouth Daily Western Mercury in 1879. Prosperous British India, Pg.128. The Lancet 16 may 1901, quoted in Mike Davis. Late Victorian Holocausts, El Nino Famines and Making of the Third World, pg 7, table P1. Maharatna quoted by Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts, El Nino Famines and Making of the Third World, pg 174. A) Dadabhai Naoroji: Poverty and UnBritish rule in India b) R C Dutt: Economic History of India c) William Digby: Prosperous British India d) DR Gadgil: Indian Industry, Today and Tomorrow. Answer: (d) Question 9: Aurobindo Ghosh was brilliantly defeated in the Alipur Conspiracy case by a) Chittaranjan Das b) WC Banerjee c) Motilal Nehru d. According to William Digby, author of Prosperous India, the flight of capital from India to England during the 19th century was GBP 6,080,172,021. At the current exchange rate of Rs 70 to a pound, it is INR 4,25,561 crores. In 1875 Salisbury, the Secretary of State, said, “As India must be bled, it must be done judiciously”. Additional Physical Format: Online version: Digby, William, 1849-1904. 'Prosperous' British India. New Delhi, Sagar Publications, 1969 (OCoLC)678743774.

| Author | William Digby |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Subject | 19th Century India |

| Publisher | T. Fisher Unwin |

| 1901 |

'Prosperous' British India, more completely titled Prosperous' British India: A Revelation from Official Records, was a book published in 1901 by British author William Digby that described the economic conditions prevailing in British India in the latter half of the nineteenth century under British rule.[1] It used official government statistics to illuminate the falling incomes and increasing impoverishment in India under British administration during that period. The book was influential and, at the time, attracted attention due to the imprinting of the actual falling per-capita income statistics in gold on the spine of the book itself.[2] The book also used government statistics to demonstrate that the death-toll and frequency of catastrophic economic disasters in India, such as famines, was growing systematically under British rule.[3]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^William Digby (1901), 'Prosperous' British India: A Revelation from Official Records, Unwin,

... Thus England's unbounded prosperity owes its origin to her connection with India, whilst it has, largely, been maintained - disguisedly - from the same source, from the middle of the eighteenth century to the present time. 'Possibly, since the world began, no investment has ever yielded the profit reaped from the Indian plunder' ...

- ^Tapan Raychaudhuri; Irfan Habib; Dharma Kumar (1983), The Cambridge Economic History of India: Volume 2, C.1751-c.1970, Cambridge University Press, ISBN9780521228022,

... As Daniel Thorner has remarked, where can one find a more dramatic presentation of conclusions than that of William Digby, who had imprinted in gold on the spine of his book the per capita income of 'Prosperous' British India in 1850 as 2d, 1882 as 1⁄2d, and 1900 as less than 3⁄4d? ...

- ^James Vernon (2009), Hunger: A Modern History, Harvard University Press, p. 51, ISBN9780674044678,

... Whereas Dutt used the Famine Commission Reports of 1880 and 1898 to catalogue a melancholy 'record of twenty-two famines within a period of 130 years of British rule in India,' Digby dug deeper into colonial records, to reveal not only that the toll — twenty-six famines in the century preceding 1900 — was even graver, but that the scale and frequency of famines had grown and accelerated ...

William Digby Prosperous British India Traveller

On 30 June 2017, many Indians will observe the hundredth death anniversary of Dadabhai Naoroji (1825-1917), an important figure in India’s struggle for independence from British colonialism and the first Indian to be elected to the British Parliament. Naoroji was a Parsi, a member of the tiny Zoroastrian community of India that today numbers only 60,000 in that country. Nevertheless, in the course of his five decades of political work, Naoroji played a vital role in uniting members of India’s diverse religious and ethnic communities into a movement for political reform and colonial emancipation.

Article by Dr. Dinyar Patel, Assistant Professor of History, University of South Carolina, and Chair, Research and Preservation Committee, FEZANA.

In 1825, when Naoroji was born in Bombay (today’s Mumbai), the British had been a colonial power in India for over eighty years, causing famine and economic disruption in many parts of the country. Naoroji was, himself, born in relative poverty: his parents migrated from southern Gujarat as its local textile economy collapsed. Through his academic performance, however, Naoroji managed to secure scholarships for attending Bombay’s best educational institutions. At the age of 28, he became the first Indian appointed as a full professor in a British-administered college, teaching mathematics and physics. He also began adopting extremely progressive positions on various social issues. At a time when most women in India lacked any form of education, he established some of the first schools in Bombay for girls. Naoroji also criticized the British government for not doing more to educate its Indian subjects.

By the late 1860s, Naoroji became deeply concerned about another matter: India’s worsening impoverishment under British rule. During the second half of the nineteenth century, India experienced an unusually devastating spate of famines that killed, by the most conservative estimates, over 28 million people.[1] While British authorities blamed these catastrophes on natural disasters alone, Naoroji pointed to another cause. He argued that there was a deliberate “drain of wealth” in India, whereby British policies were siphoning capital out of the country and thereby pushing Indian subjects to the brink of starvation. Collecting and tabulating a wide range of economic statistics—while also disproving the rosier statistics compiled by British officials—Naoroji calculated that the average Indian was, by the 1880s, too poor to buy enough food for a mere subsistence diet. Under British rule, he declared, India had become “the poorest country in the world.”[2]

William Digby Prosperous British India Wikipedia

Naoroji’s “drain theory” caused a great stir in both India and Great Britain: it provided concrete proof of colonialism’s devastating effects upon India, rubbishing British claims of benevolent imperial rule. His writings influenced a generation of Indian and British thinkers, including several prominent British socialists. In time, Naoroji’s writings reached a wider audience across Europe and North America, becoming important resources for incipient anti-imperial movements. For example, William Jennings Bryan, the American Progressive leader, cited Naoroji’s drain theory to explain why he opposed American annexation of the Philippines after the 1898 Spanish-American War.

Having laid out his economic critique of British colonialism, Naoroji forayed into politics. In 1885, he helped found the Indian National Congress, the political party that eventually led India to independence in 1947. Naoroji strove to make the Congress as inclusive as possible. As president of the organization in 1893, for example, he famously stated that, “Whether I am a Hindu, a Muhammadan [Muslim], a Parsi, a Christian, or of any other creed, I am above all an Indian.”[3]

But Naoroji did not just limit his political activity to India. Recognizing that imperial policy was formulated in London, he decided that the best way to influence this policy was to put pressure on the system from the inside. In 1886, he stood for election to the British Parliament as a member of the Liberal Party.[4] Although he lost the election, he generated widespread support among progressively-minded Britons, including suffragists, Irish nationalists, labor leaders, and socialists—individuals who lent their support for India’s political aspirations.

A few years later, in 1892, Naoroji stood for election once more, this time from the constituency of Central Finsbury in London. It was a grueling fight: Naoroji’s opposition lobbed racial barbs at the Indian candidate, while the Conservative prime minister of Great Britain, Lord Salisbury, urged voters not to send a “black man” to Parliament. In the end, Naoroji won the election—by a mere five votes (he earned the sobriquet “Dadabhai Narrow-majority”). Regardless, his victory generated headlines around the world, especially in India. When he returned to India in 1893, crowds in Bombay, Delhi, Allahabad, Lahore, and elsewhere celebrated him as a national hero.

William Digby Prosperous British India Coin

Naoroji’s reception in the British Parliament, however, was much more frosty. He continued to face racist opposition. His pleas for Indian reforms fell upon deaf ears, and his efforts to legislate change garnered little support. In 1895, he lost his reelection bid. Disillusioned with parliamentary politics, Naoroji became more radical, pronouncing British policy in India as “evil” and “a curse,” especially in light of a new spate of famines afflicting the country.[5] In 1906, serving as president of the Indian National Congress once more, he declared that the time had come for Indians to work towards achieving swaraj or self-government. There could be no more time lost on incremental political reforms. Self-government, he stated, was the only way to stop the devastating drain of wealth that had crippled India.

Naoroji retired from politics the following year, at the age of eighty. He left behind a Congress party organization that, in spite of significant internal divisions, was growing more robust and politically confident. His analysis of Indian poverty, claiming that British imperialism was inherently exploitative, became a central tenet in India’s struggle for independence. In addition, he mentored and influenced a new generation of Indian leaders that finally brought an end to the colonial regime. One such leader was Mahatma Gandhi, who had received Naoroji’s assistance while campaigning for the rights of Indians in South Africa. A few months after Naoroji’s death, Gandhi summarized his legacy: “Dadabhai’s flawless and uninterrupted service to the country, his impartiality, his spotless character, will always furnish India with an ideal to follow.”[6]

Further Reading

William Digby Prosperous British Indian

Masani, Rustom P. Dadabhai Naoroji: The Grand Old Man of India. London: G. Allen & Unwin, Ltd., 1939.

Mehrotra, S.R. and Dinyar Patel. Dadabhai Naoroji: Selected Private Papers. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Naoroji, Dadabhai. Poverty and UnBritish Rule in India. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1901.

Patwardhan, R.P., ed. Dadabhai Naoroji Correspondence, parts I & II. New Delhi: Allied, 1977.

[1] These estimates were for the years 1854 to 1901. William Digby, ‘Prosperous’ British India (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1901), pp. 129-30.

[2] “Famine in India: Address by Mr. Dadabhai Naoroji,” India, 1 March 1901, p. 103.

[3]Speeches and Writings of Dadabhai Naoroji, ed. G.A. Natesan (Madras: G.A. Natestan & Co., 1917), p. 59.

[4] Due to the lack of clearly-defined policies on citizenship, it was possible, in those days, for a British colonial subject to stand for a seat in a British constituency, and several Indians did so from the 1880s onward.

[5] Private correspondence, Dadabhai Naoroji Papers, National Archives of India, New Delhi.

[6]Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol. 14 (Delhi: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, 1965), p. 61.